(Excerpt from chapter one)

1 What has Grandmother Eva got against Pecorino cheese?

Lately – though I can’t be certain it hasn’t been going on for a long time – new arguments have erupted between my grandmother and grandfather, strange and unnecessary, whose point or cause are unclear to me, but they’re becoming increasingly frequent. Sometimes Ernest becomes so angry at Eva that he, trembling, asks me, who’s trapped between them, to help him stand up and take him away from here, or, if I don’t have time for that, at least call a taxi for him, because he wants to get out of here, just get out, and Eva again needs the car.

To where? But it’s a rhetorical question. I know: when Ernest wants “to get out of here,” he wants to go to Café Aroma on the ground floor of the mall. If nothing else, he’ll at least sit drinking coffee with the other pensioners, from Argentina, who spend long hours there every day and who may be his only friends, in addition, perhaps, to Effi, the new neighbor across the hall. Julio and Sergio, Isaac and Josef have for many years commandeered the same square corner table between two banquettes upholstered in red that meet at a right angle. The group likes sitting there not only because it’s their usual spot, but because it offers an excellent view of everything before them and they can see everyone who leaves and enters the café – mostly young women with children’s strollers, occasional soldiers with kitbags and weapons, getting a bite while standing and then hurrying on their way – and in particular, they can see the faces of their favorite waitresses whose young bodies are concealed almost to their open collars by the counter that’s too high for them. From their corner they can all – Julio and Josef, Sergio and Isaac, and also Ernest, whom they call Ernesto – loudly comment on life and on the situation, on the past and on the future, on politicians and sports figures, all in a muddle of Hebrew and melodic Argentinian Spanish that everyone except Ernest understands. And when two mature women approach them – excessively mature, not like their Hagit, who’s already worked for Aroma six months – and bend toward the five old men and jointly ask them angrily, like a pair of local Humpty-Dumptys, “Please talk a little more quietly because you’re not alone here and there are other people besides you,” Julio smiles his best smile at them and placates them, “Fine, Madame and Madame, we’ll speak more quietly,” and mutters as they walk away, “Brujas!,” Witches!

Five minutes later they’re back to their usual volume. Their loudest discussions are about politics – because what else do they have to yell or complain about other than their pensions shrinking as the years go by because of the government’s irresponsibility, about the ridiculously low interest rate the bank pays on their deposits, about the parasites destroying the country, and about the Bibi the prime minister, whom only Sergio is pleased with – “Health, that’s what’s most important, nothing else is as important as health, ijo, without it nothing helps.” But there’s still a wildness about them, an electricity that even if not physically expressed in their flabby bodies is clearly manifested in their sharp tongues, their booming voices, their joy in life aroused by the coffee and the camaraderie – together they’re a true force – and easily ignore the glares of young mothers, because so what if they woke some baby? An entire life awaits it; and anyway, they’re longtime, daily customers at Aroma, no one will ask them to leave so others may be seated.

Their vitality dissipates only on their way home, to slump facing the television set, in the kitchen or living room, in a starkly echoing house grown too large for them. Meanwhile, everyone in the café hears them even if they don’t want to. They order two rounds of strong coffee and also eat open-faced tuna or salmon sandwiches (only Julio always orders a piquant Tunisian sandwich which is never spicy enough for him) and Hagit, the petite Aroma employee who’s saving money for university and has already taken a really amazing trip to South America, comes over from time to time to ask, “Is everything OK amigos, do you need anything else?” Although the café doesn’t offer table service - she simply enjoys chatting a bit with them in her poor Spanish. And it’s Isaac, that devil, who doesn’t speak much but whose focused gaze is always intent on her décolleté and he’s the only one who doesn’t keep affectionately saying to her, C’mere, Rubia! – C’mere, Blondie! – he’s her favorite. A satisfied look wafts over Isaac’s face during the brief moments Hagit spends with them, just before she smiles winningly at these old men, who’ve long forgotten what such a smile feels like, and returns to her place behind the counter.

Ernest enjoys joining Julio and Sergio and Josef and Isaac even when he has no reason to be angry with Eva his wife, and even if she hadn’t made him so mad that he’ll rise from his seat in suppressed rage and want to leave the house despite the hassle involved. Even Amotz has already realized his grandfather joins the group at Aroma only after pretending he’s headed elsewhere; that he’s passed the café’s entrance by chance, very surprised to see the equable Sergio, whose disheveled hair is blindingly white and who waves to him with his good hand; who, unlike Julio, doesn’t suffer from rheumatism, gracias a Dios, and whose stroke this past November affected his other side. And Ernest doesn’t relent until Sergio pleasantly calls to the tall man, “Buenos Dias, Ernesto, come join us…” And he immediately moves his bulk to the left and, like a chain reaction, Julio pushes Josef who pushes Isaac while they’re all saying “Hola, hola Ernesto,” and the red plastic upholstery beneath them is revealed like a scarlet tongue surreptitiously licking their bottoms.

“Grandpa, is everything alright?” I ask. The left half of my grandfather’s face is reflected in the screen of the unlit television set standing in the living room – drooping near the corner of his mouth. His mouth has sagged slightly since his very mild stroke. Mild as it was, it left its mark, even though, thankfully, neither his speech nor movement was affected. It was his spirit that suffered the hardest blow.

“Everything’s fine,” Ernest replies.

Everything’s always fine in the Bloom family, even when nothing’s fine.

Ernest is pensive. All morning he had rebelled at the relentless reckoning imposed upon him by sitting so long facing the shutters. He’s glad Amotz has come, and isn’t sorry to interrupt his meditative conversation with himself, its essence all that now remains. He knows that as soon as his grandson leaves he’ll return to the question that has troubled him for some time, because what’s really the bottom line of the profit and loss statement of his life’s account? Is there even any point to such accounting? When he’s alone and occupied with his thoughts, old and new, time’s deceptiveness surprises him – how quickly it passes, how slowly. Today, for example, time stands still, as if its hands are frozen in their circuit – neither seconds, nor minutes, nor hours, only a viscous concoction of being; and it occurs to him that if the mythical Egyptian scarab beetles had really existed they also might have been unable this day to roll the sun down from its heavenly heights and bring today to a close. Perhaps, Ernest thinks, because he’d waited for Amotz all day; perhaps because the trunks of the cypresses outside, which had thickened, no longer sway in the wind and their immobility paralyzes him. It’s good the lad finally came.

But not only are Ernest’s days charged, so are his nights, during which he’s occupied with dreams bursting within him like rushing bubbles. He retains only faint impressions of them, like the taste of something he’d eaten years ago which had dulled but hadn’t fully disappeared. He still tells no one: Nora comes to visit him at night, she’s young and beautiful, he smells her flesh, tastes her blood and they excite him now as much as they did then, and the blood tastes sweet on his tongue as it did that day, at the Hotel Malta. At first he tried to deny how Nora suddenly arouses him at night while he sleeps. Now he’s willing to admit to himself that Nora comes to him almost every night and when he opens his eyes toward morning, just before light breaks, he feels himself burning inside, excited, tingling in ecstasy, and he must wipe away the unbidden smile on his lips and the tears awaiting their turn. His groin also seems responsive. He’s not embarrassed, quite the opposite, it’s just that he doesn’t know what he’ll do with the hesitant desire renewed within him. His Eva has long been wooden.

Eva also senses what he tastes in his sleep. Today, for example, while they were still in bed, she turned to him, her face lined with wrinkles, appearing, as she lay, like fabric stitched too tightly, and asked in her hoarse morning voice, “What happened, Ernő, did you dream about girls again?” then questioned him, her brow furrowed, “Tell me, how many sleeping pills did you take yesterday evening?”

Again and again Ernest calmly answers, “I haven’t taken any sleeping pills in a long time, Evikém, I really haven’t. I haven’t needed any for a long time.” While Eva had already dressed and combed her hair and, vigorous for a woman her age, as everyone tells her, turned her back to him and sat before her old vanity mirror under the window. Her face washed, and bathed in sunlight, she drew across her upper lip the tip of the lipstick whose purple hue was so dark it was almost an ugly brown, and pressed her lips together so the greasy cream reaches the edges of both dry lips. She looked at her husband in the mirror and said, “It’s not possible, Ernő, that you aren’t taking pills. You’ve been sleeping very soundly recently, you’ve even stopped snoring.” Eva’s lipstick slid back into its golden tube like the red bit of flesh that quivered between the legs of Tibi, their German shepherd – who’d been a true Don Juan and died in ripe old age still possessed of all his senses and passions – had withdrawn into its sheath. Eva thrust her chin at her reflection. Her colored lips looked cold to her, almost blue, but she was nevertheless satisfied by the result. Then she sank her face in the other mirror, which magnified, to more easily pluck the three stubborn hairs sprouting at the bottom of her chin. Her eye in the mirror seemed like a fish slipping through the water of a lake and every wrinkle on her face swelled and deepened. And she recalled Tibi’s regular seasons of heat and how he’d sit on all fours with ears pricked, tongue hanging, panting, and suddenly the piece of red flesh would slide out between his legs and his hairy member moved between his legs in time with his breathing and suddenly blossomed brightly red. They’d laughed in embarrassment, but didn’t look away from the unsheathed flesh, and even before their embarrassment made them blush the scarlet bullet disappeared as if it had never been, and Tibi rose and rushed at the front door and opened it by himself before slinking out.

Eva left. Eva exits and Nora enters. Nora enters and Ernest softens again. The silence is so good for him, such good silence, that he shuts his eyes and wrinkles his nose. Futilely he tried to recapture the scenes of the dream he’d had when he slept. More than he desired to recapitulate the dream in his mind, he wanted to home in on the split second when he’d opened his eyes and his bones and heart had been saturated with lost time, and occasional flutters of fragrance, and people no longer here, and a woman whom he’d once loved with all his heart. It’s true, he admits – for some time now only thoughts of Nora free the winged stallion caged within him. That’s why he wants to talk to Amotz; because of the stallion tossing its mane inside him and stamping its hoofs in his guts. More than once he’s tried to hush its neighs so Eva won’t hear.

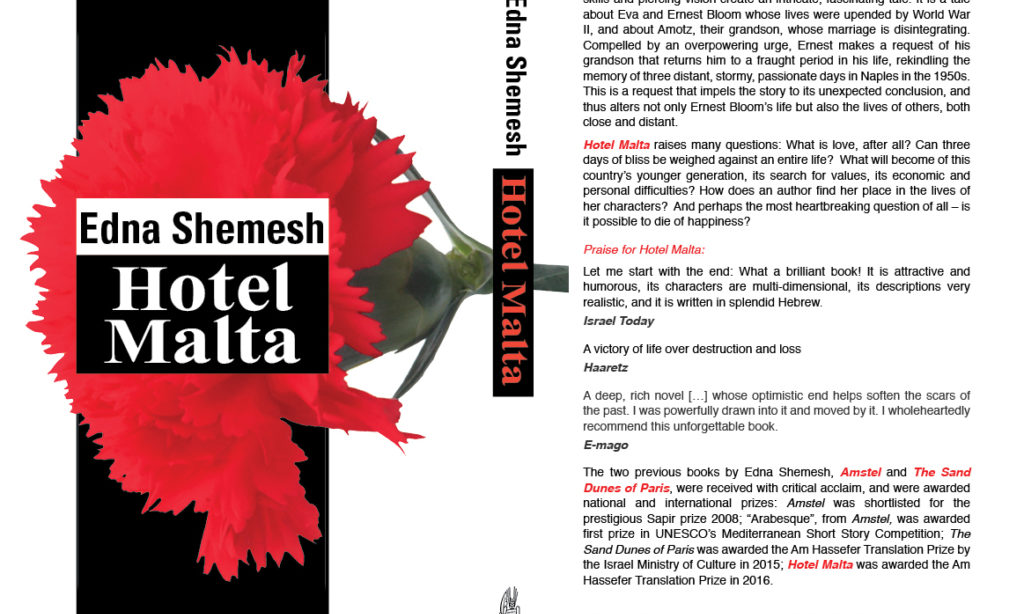

Excerpt from Hotel Malta by Edna Shemesh. Translated from Hebrew by Charles S. Kamen

Copyright © 2015 by Edna Shemesh. All rights reserved to the author. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the author.