It was a different world: February of last year. We were in the final days of American ignorance about how profoundly COVID-19 would change everything. At the time, we thought maybe it would be like SARS, or Ebola, or some other foreign epidemic that we could keep out of sight and out of mind. The bigger news story was the presidential election, and as I drove over the state line from Massachusetts on my way to MacDowell for a two-week residency, the yard signs presented a clear snapshot of the political geography of southern New Hampshire. Rindge, just over the border, looked like Trump country, and my mind flashed to the darker readings of New Hampshire license plates — Live Free or Die — and the (apocryphal) rumor I grew up with in the suburbs of Boston — that everyone in New Hampshire owned a gun.

Back home in my progressive bubble in Brooklyn, the keywords of politics were justice, equity, maybe even structural change. But the last 40 years had calcified the terms of another narrative in a different geography: independence, freedom, liberty. These words used to correlate with justice and equity, of course, but somewhere along the line, equality became something Democrats cared about; whereas for Republicans, it was supposedly freedom.1

Live Free or Die. Really? When this state motto was adopted in 1945, I suspect its proponents were not thinking about enslaved people. They were trying to conjure an image of John Stark, a Revolutionary War hero from New Hampshire who invoked a sentiment borrowed from the French Revolution to excuse his absence from a party.2 In 1971, a new state regulation mandated the motto appear on all non-commercial license plates. Previously, they had read, simply, “Scenic…”

As I turned onto Route 202, I tried to turn off my brain (and the radio). I was clearly too addled by obsessive attention to the Democratic primary to prepare for the gift of time that I was about to enjoy. The moment had come to think about what I was going to New Hampshire to write. Put most simply, it’s a book about housing and a particular set of ideas about how to improve the living conditions of extremely vulnerable people. Undergirding this history is a broad reading of various philosophies of dwelling — of what a home is for — that excavates the origins of Western notions of private property and connects some very old ideas to 20th and 21st century debates around the world about rent, ownership, and economic opportunity.

I was going to New Hampshire to write and read and think about these things. I cleared my throat and stiffened my spine in my borrowed Subaru. I reminded myself I was headed into an intense period of production. After all, this was to be the first time I was spending more than a night away from my son, who was one and a half at the time. Two weeks away was a big ask of my partner and certainly needed to be justified by a large amount of progress made. These were the mental preparations I was making. I did not prepare myself for the community I would find.

Within minutes, a more picturesque and iconic New England landscape came into view. The big box stores and four lane roads at the state border gave way to steeper topography, older and larger homes, and yard signs for Buttigieg, Warren, Sanders, Klobuchar. (I saw no Biden signs in New Hampshire.) I would soon learn that the turn for MacDowell was just after the house with the “Amy for America” sign. I got to the office just before closing on a Friday afternoon, eager to settle in and exploit my newfound and temporary “freedom.”

Freedom to create. MacDowell’s motto. The preposition in the middle of that phrase makes it sound like a positive liberty, Isaiah Berlin might remind us, involving the presence of control or self-determination. Freedom from the barriers to creation; now that would be a negative liberty, involving the absence of obstacles or interference. The latter kind is the one that has evolved to align itself with the notion that government is an impediment to freedom. Or to put in the simpler terms of Reagan’s inaugural address: “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

In the months after I left MacDowell, with ambulances a constant presence on my block in Brooklyn and nearby hospitals over capacity, “freedom” was invoked by those who didn’t think the government had any business limiting personal mobility or assembly, or mandating simple protective measures like masks.

As an urbanist, I think a lot about government, about collective action, about what we owe to people whom we do not know but with whom we share space, be it a sidewalk, a school, a subway ride, or an elevator. During lockdown, voluntarily sharing any such space with strangers became a reckless risk. Those of us fortunate enough to work from home were stuck in our neighborhoods, but the social corollary of this physical domain — community — had become a luxury none could afford.

But on the February Friday when I first arrived in Peterborough, the coronavirus was still a distant thought. I washed off the road and got acquainted with my studio, the locus of my freedom. Then, I walked up the hill to dinner. What I found there was fellowship. While the freedom to create felt like the opportunity for generative solitude, I came to appreciate even more the freedom to connect, to build community, however temporary.

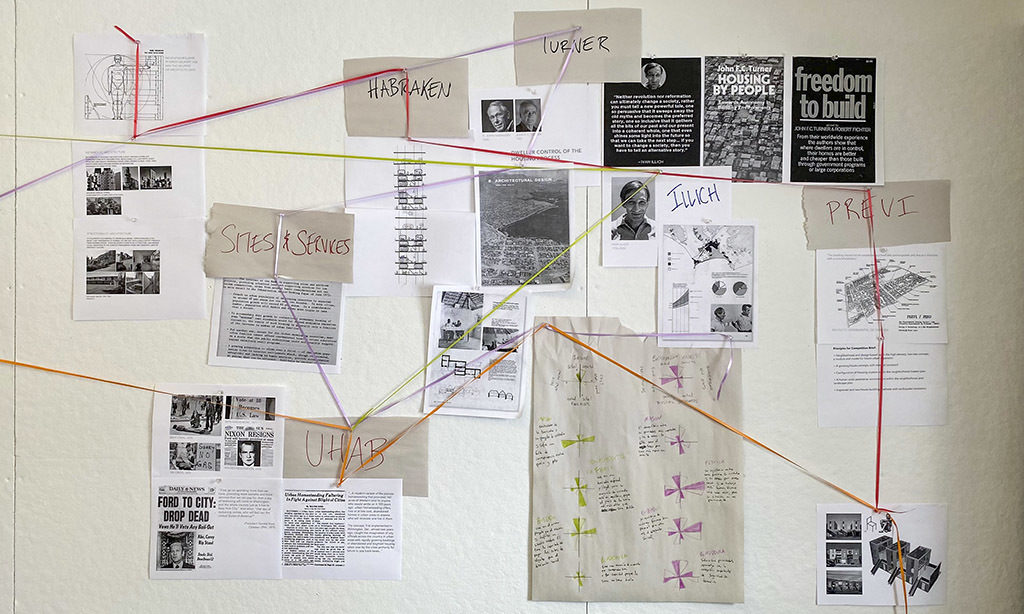

I majored in visual art in college, regularly pulling all-nighters in the dark room or the film editing suite. Part of my work continues to include making video installations for museums and exhibitions. I teach filmmaking to students of architecture and urban design. But it had been a while since I was surrounded by peers whose creative energy wasn’t singularly focused on urban policy change. My work these days is primarily concerned with tracing an intellectual history of a specific approach to providing housing in poor communities around the world. I spend more time thinking about maybe attending zoning meetings than gallery openings. So to be surrounded by poets, painters, performers, composers, was thrilling and felt new.

Small talk became studio visits, walks became brainstorms, and then feedback became friendships. The strength of these fast-formed bonds would certainly be tested by the months to come: no promises of attending play premieres, open studios, or readings could be honored during COVID. But the abrupt loss of these and so many other types of socializing and collaborating as the pandemic raged cast the gift of these new relationships in sharp relief. The freedom to connect, to find and foster fellowship, proved to me to be the greatest gift of a space dedicated to enabling the creative spirit to thrive. For me, personally, it turned out to be less about removing distractions and more about providing new kinds of conversations.

Because we don’t really do anything alone. No, not even artists, despite what our art history textbooks tried to make us believe. Some of us are fortunate to spend lots of time alone, making stuff. And an even smaller proportion sometimes get the opportunity to leave their daily circumstances and make stuff without the limits imposed by regular life: work and family obligations, making meals, noise, emails. But those of us who get to do that do so through the luxury of paying caregivers, through the relationships that open doors or remind us of upcoming deadlines, and through the support of institutions with staff. (In this country, we also do it all on unceded land — MacDowell is on Penacook Abenaki territory — in an economy built with stolen labor.)

I believe art will continue to be a source of inspiration. Art has the unique possibility and responsibility to reflect and refract human experience in ways that can be sacred or intimate or monumental precisely because it lacks a specific instrumental utility and yet still manages to foment the narratives — the radical imagination — that propel us forward. But it has to be in coalition with people who claim a different vocation or mode of expression. It has to name, or at least to honor, the alliances on which its creation relies. It has to come with some resistance to the mythos of independence and a lot more recognition of interdependence. Maybe it’s less about liberty. Maybe it’s more about solidarity.

MacDowell was supposed to be my time away from people to write. Little did I know that it would actually be the last time I was in a community of strangers for a year and a half. And in fact, it wasn’t freedom from those interactions and interpersonal connections that freed me to write; it was the opposite. What I found wasn’t freedom. It was communion.

1 https://www.salon.com/2017/07/09/conservatives-claim-to-love-freedom-but-the-historical-record-and-the-evidence-suggest-otherwise/

2 https://www.nh.gov/almanac/emblem.htm

Get notified when the next essay is published

Find all Why MacDowell NOW? essays here

Cassim Shepard is an urbanist, filmmaker, writer, and editor. He also consults for non-profit organizations — especially those concerned with urban policy, architecture & design, and arts & culture — on editorial and media strategy, public engagement, and urban planning projects.