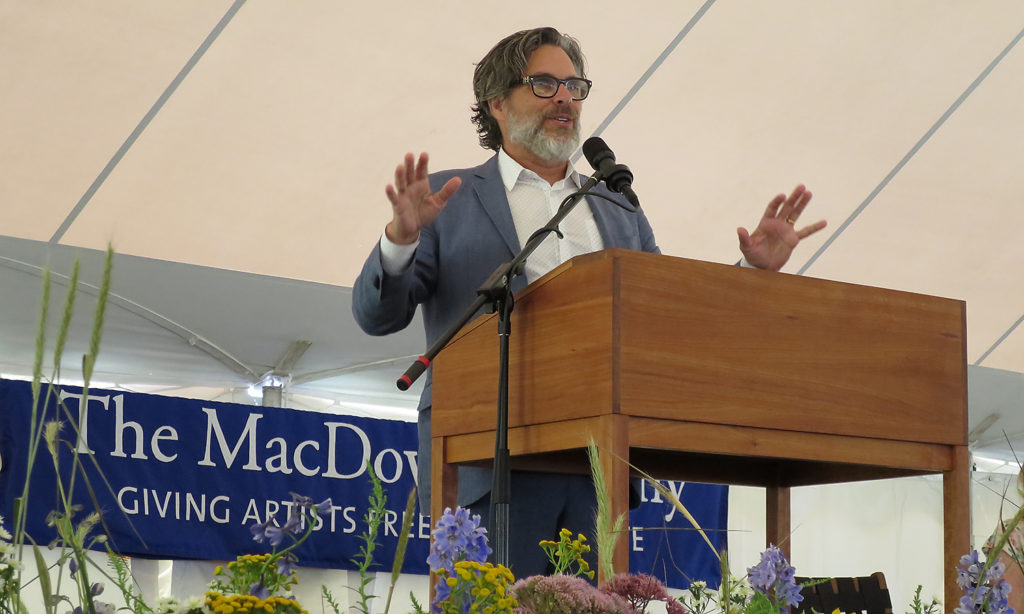

Transcript: Medal Day Welcome Address by Michael Chabon on August 13, 2017, at MacDowell

You can watch the video of the welcome address here.

It’s a rare and a sobering thing, in life, to be given, and to know ahead of time that you have been given, a chance—one chance—to tell a perfect stranger how grateful you are for their existence on the earth. Over the past six Medal Days there have been a couple that stood out as opportunities of that kind for me, and in those years the speeches I made were so much more difficult to write. I started them, gave up, started them over again. And in the end, felt I had not even begun to get at the depth of my gratitude.

That’s why it was so very kind of our 2017 MacDowell Medalist, David Lynch, to decline our invitation to appear in person today. (laughter) Now of course Mr. Lynch explained, with due regret, that he was obliged to decline because of a long-planned family vacation, but really—he was just doing me a favor. Lynch’s first feature film, Eraserhead, blew my seventeen-year-old mind the first time I saw it, at a midnight showing at the Pittsburgh Playhouse in early 1981. Blew it in ways that I have yet to recover from. Twin Peaks forever rewired the circuitry of the apparatus I use to scan and interpret American life. And I’m just going to totally nerd out on you people, now, and confess that I have seen Lynch’s 1983 adaptation of one of my favorite novels, Frank Herbert’s Dune, at least five times, and I have never failed to totally dig it. If the man were going to be sitting right to my left today, I would have faced a solid week of writing and re-writing, pondering and re-pondering, deleting and giving up and starting over, hoping to take advantage of my one shot and do justice to all the things in his work that I’m grateful for. Instead I just tossed this puppy off in a night or two. (laughter) What a relief! I can say whatever I want! I could talk about how much I like his recordings of zither music or his series of documentaries about the history of needlepoint, the guy would never know.

To see what is in front of one’s nose, George Orwell famously said, needs a constant struggle. Think about that. To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle. The human mind—that ancient, dubious assemblage of learned and inherent biases, habits of sensory triage, and cognitive rules of thumb—has been so traumatized by the unremitting grim truths of evolutionary and human history, perhaps, or so contrived by the mocking hand of a cruel prankster of a god, as to become resistant to truth. It’s because of this doubtful gift of being able to wish away and ignore the cold, hard, cheerless facts of existence that, as individuals and as nations, we are continually surprised by calamities, defeats and disasters that in hindsight ought to have been—were—obvious all along. When the ice caps melt, and the lowlands flood, and species collapse, and earth turns inhospitable, those who survive will look back and say, How could they have missed this? How could they not have known? Wasn’t it obvious? And the answer, of course, will be: It needs a constant struggle to see what is in front of one’s nose. A constant struggle: who has the strength, or the time, for that? Those among us who are equal to that struggle we call “prophets,” and in general we treat such people very shabbily.

And that’s just when it comes to what’s right in front of your nose—the plain truths, the indisputable data, the behaviors that speak for themselves. If even seeing those things requires constant struggle, what about the ambiguities? Let’s say you step up, as a concerned citizen and devotee of truth and lover of humankind, to undertake the constant struggle of seeing what is right in front of your nose. What about the hidden truths, the buried drives and desires? The things that lie beyond distant doorways, behind the curtains of dreams, deep in the sea-bottoms of memory? Who’s going to see all that, while you’re busy looking just past the Orwellian tip of your nose?

Over the past half century no one has taken a harder, clearer look behind those doors, beyond those curtains, and into those deep oceans than David Lynch. “My childhood,” Lynch has famously said, “was elegant homes, tree lined streets, the milkman, building backyard forts, droning airplanes, blue skies, picket fences, green grass, cherry trees. Middle America as it’s supposed to be. But on the cherry tree there’s this pitch oozing out—some black, some yellow—and millions of red ants crawling all over it. I discovered that if one looks a little closer at this beautiful world, there are always red ants underneath.”

To see the ooze and the swarm: the weird in the everyday, the horror just beneath the ordinary surface of things, the freak show in the supermarket, and, even more powerfully, to find dark beauty in that freakiness and horror—I want to extend Orwell’s dictum and say that this, too, needs a constant struggle. And yet that isn’t really true. Moments when we manage to see what is in front of our noses—say, the degree to which our strongest beliefs are based on wishes and fears, or the racism and misogyny that undergird our most powerful institutions—those moments are rare, and hard-won. Some of us never manage those moments at all. But each of us—even those who might walk past that cherry tree a hundred times and never see the raging boil of ants, even those of us who try to maintain a healthy distance between ourselves and the freaks and the horrors—every single one of us slips into the weird, easily, helplessly, with astonishing freedom, every single night of our lives, with no struggle at all.

“In dreams,” as Roy Orbison sings, so memorably, on the soundtrack of Blue Velvet. In our nightly dreams—our weird, dark, beautiful, freaky and horrifying dreams—we are all David Lynches, our gazes unflinching and patient and curious, dispassionate, uncensoring, reporting without judgment or reservation on the blue velvet violence of our thoughts and the deeply strange organ that thinks them. In dreams, once we’ve been visited, as Orbison horrifyingly and Lynchesquely put it, by that candy-colored clown they call the sandman, we all gaze without flinching through the sea-depths of our darkest fears and wishes, behind the curtains and doorways of the daytime rationalizations and evasions and taboos.

That part’s easy; the struggle comes when someone tries to wrestle those truths, the night-truths, into the light. I’m not talking about tricks like the use of forced perspective, Dutch angles, over-reliance on dwarfs and shadow-puppets and talking animals and all the other conventions that artists—including David Lynch—have employed over the years in an ultimately doomed attempted to capture the “dreaminess” of dreams. To be honest, I kind of hate that stuff. I’m the kind of guy who fast-forwards through dream sequences in movies and in books skips to the end of dream paragraphs. All that is easy enough, too. The truth of a dream is not its dreamlike quality: the truth of a dream is a tree bleeding ants through a gaping wound. It is, in other words, the truth right in front of our noses, which often enough we can’t see not because of our vanity or self-delusion or fear but for the simple reason that we go through life with our eyes closed. We call the people who remind us to open our eyes, “artists,” and in general we don’t treat them a whole lot better than we do our prophets.

But at MacDowell, we like to feed them, (laughter and applause) and shelter them, and make sure their chairs are comfy and their light is adequate and their beds are soft enough for dreaming. Every year, we give one of them a Medal. This year that medal is going to an artist who has been opening our eyes and aiming our gazes to the night-truths of the world for the past forty years. Since he could not be here with us today, I’d like to invoke the spirit and power of his work now by asking you to turn to your neighbor, the person in the seat beside you or behind you or in front of you, and… imagine that in place of a head, he or she has an enormous horseshoe crab… (laughter) go on. Now, reach out and gently take hold of their right tentacle with your own… OK, are we doing this? And say, “I have complicated feelings about wildebeests.”

In the name of David Lynch, the 2017 MacDowell Medalist, I wish you the truth of your dreams, violent and dark and beautiful as that truth may be, and the strength and the courage to face it. Thank you. (applause)

Read journalist Kristine McKenna's introductory speech about David Lynch