Sculptor who became inventor and director of Center for Innovation and Applied Technology at The Cooper Union has creative work archived.

When The Smithsonian Institution proposes to establish a permanent archive of your papers, it’s a safe bet you know what specific papers they mean. For MacDowell Fellow Robert Dell, it could have been for those he generated as an engineer, inventor, author, or sculptor.

“It was a pleasant surprise,” Dell says of the request from The Smithsonian. While that occurrence might satisfy most people who have dedicated more than 30 years to a particular field, it’s the sculptor in Dell who says he finally feels that his work is being fully recognized.

Dell, who is the Founding Director of the Center for Innovation and Applied Technology at The Cooper Union in New York City., started as a sculptor who appreciated the beautiful and complex relationship between science and art. His initial use of diverse elements, including metal, electricity, and crystals as integral parts of artistic works influenced his later career in engineering.

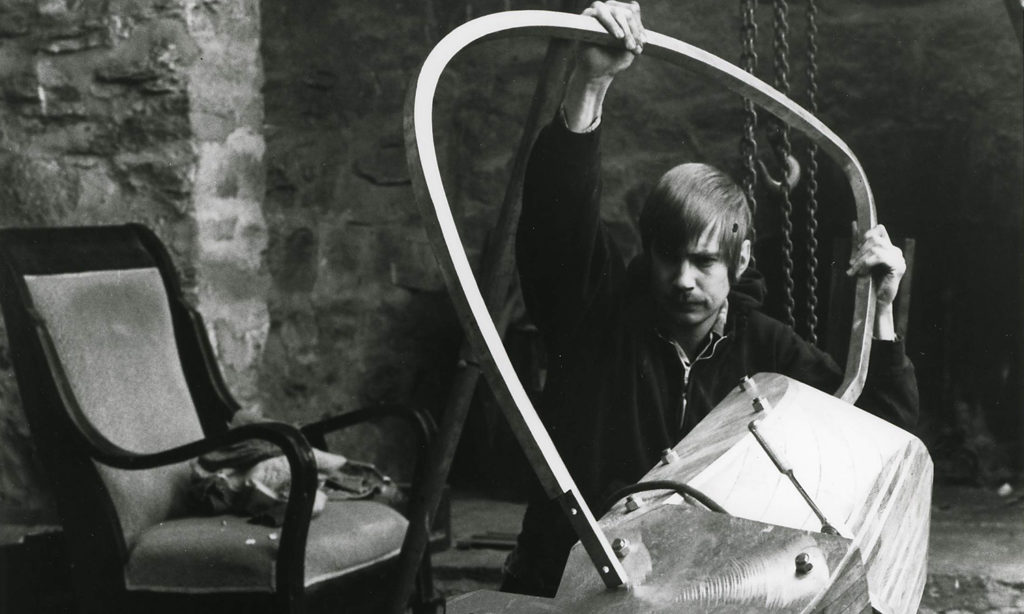

While working in Alexander Studio in the spring of 1980, Dell needed special heavy-duty electrical supply lines routed to the studio for his welding equipment. The MacDowell Colony accommodated the request and Dell created two large-scale sculptures, Talus and Bellerophon. Titled after Greek mythological characters, Dell’s work sought to embody man’s neglected essential connection to the Earth. His work at that time was influenced by artists such as William King, who was a good friend and a MacDowell Fellow in 1977, and Issac Witkin.

Dell credits The MacDowell Colony for validating his exploratory creative work. That, he says, eventually opened doors into the engineering field and led to his success with geothermal sculpture and ultimately to green energy research.

“I owe an unpayable debt to MacDowell for planting the seed,” he says, that helped nurture his unique specialty. His visual art over the next 30 years was the subject of articles and reviews in The New York Times, Leonardo, Sculpture, and Iceland Review, and it’s been featured in many solo installations including places such as Harvard, MIT, and the Reykjavik Municipal Art Museum. His geothermal installations have occurred at Yellowstone National Park and at Iceland’s Krisivik Protected Area and their Great Geysir.

His best known work is the first geothermal-powered sculpture that was created and then powered by hot springs during a Fulbright Senior Research Fellowship to Iceland in 1988. The title of the work, Hitavaettur, means “guardian of geothermal hot water” in Icelandic. The sculpture was inspired by the artist’s desire to create a “mythological personification of the Earth’s energy using today’s technology.” It is now powered by the same geothermal hot water that heats the city of Reykjavik.

“Simply put, he borrows geothermal energy to fuel his art,” said art critic Dominick Lombardi. An innovative thermocouple system is used to create electricity from the change in temperature between the internal heat and the surrounding air. The electrical current powers LED and laser lights in a quartz crystals and liquid crystal panels change color depending on weather. The structure, complete with metallic internal “organs” has an outer skin warmed by its circulation system, adding a comforting element to what Dell calls a biomorphic entity.

“Our technological society has made a concentrated effort to control the uncontrollable – nature,” Dell has said in his artist’s statement. “I am personally distressed by our blatant disregard of our life support system that sustains us all – the Earth… [my sculptures] are visual ballads that gently sing the earth’s song to those that want to listen.”

Health issues have affected Dell’s ability to visualize his art, and he has transferred his creative energies to engineering and writing. “All my work is basically related,” he says, explaining away what might seem like a long leap from one discipline to the other. Both are about finding “simple and elegant solutions to complex problems” and, he says, his desire to reduce waste and to promote the use of renewable resources was the ultimate connection between the two careers.

Dell has developed several green energy technologies, including an outdoor system of heated ground agriculture that was constructed and has been tested at the Agricultural University of Iceland in Hveragerdi since 2007 and in New York City since 2008. He’s also incorporated waste heat in green roofs in New York, enabling green grass through the winter in addition to a small cotton harvest.

In addition to the Fulbright, Dell has received an American Scandinavian Foundation Fellowship and an appointment as Research Fellow at MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies. For his green engineering work, Dell has received numerous grants from Consolidated Edison, additional academic appointments in Iceland, and was Honorary Research Associate at the New York Botanical Garden. He is the first inventor of 10 patents and is first author of many peer-reviewed engineering research papers on his green geothermal technology for venues including the American Society of Mechanical Engineers and the Geothermal Resources Council.

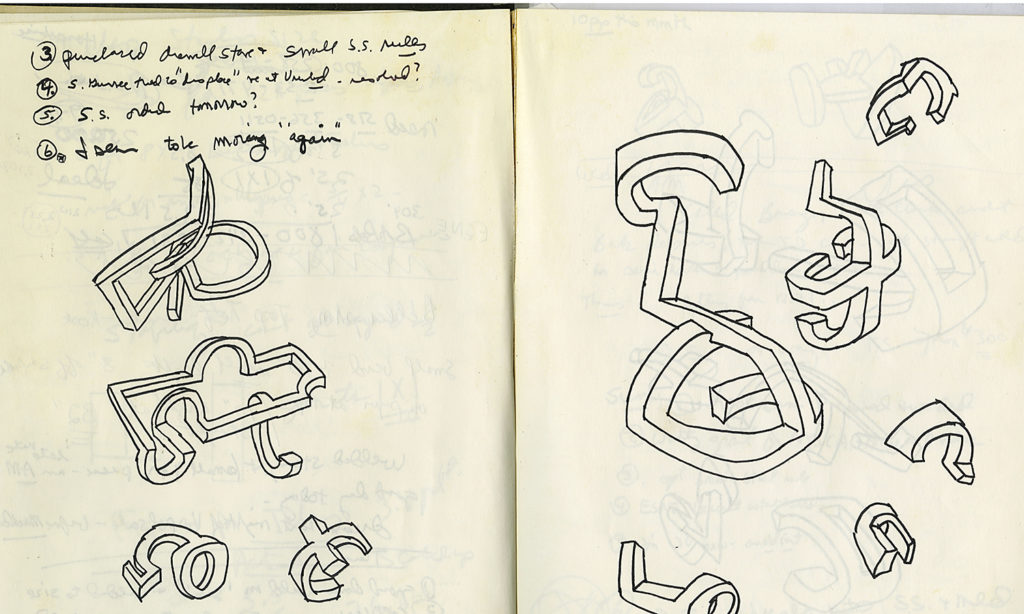

While Dell was “disappointed” by the lack of interest that his sculptural research and work received at the beginning of his career, MacDowell, he said, showed him that he had value in his chosen discipline and it also provided many fond memories to get him through many tough times. Since his residency, it’s no secret there’s been a surge in environmental awareness and geothermal energy research. The Smithsonian has now recognized him as a “progenitor of sustainable art” and for his geothermal installations. As a result, Dell is happy to see that his MacDowell Colony journal and sketches, correspondence, project proposals, and personal records will be among “The Robert Dell Papers” permanently stored as part of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.