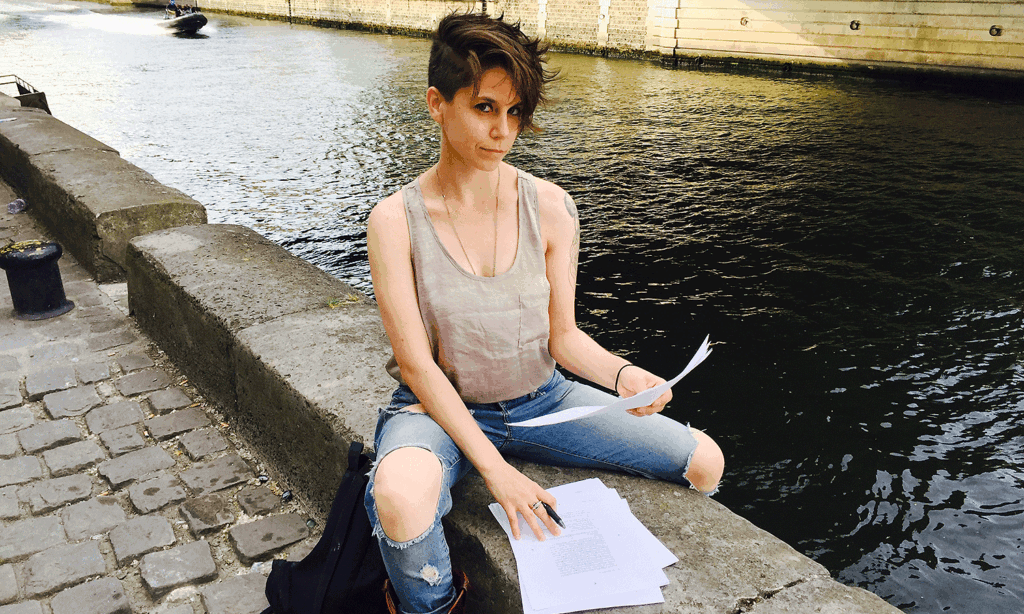

It’s early spring in Paris, and the days are cold and rainy. When the sun comes through, the whole city sprawls along the banks of the Seine, sun-dazed and hopeful. I’m here to do some research for my second novel, but on the mid-afternoons in which I decide not to work, I wander the city. At the Pompidou, I stand in front of Niki de Saint-Phalle’s La Mariée for a long time; it is a looming sculpture of a grotesque, sad woman in a wedding dress. I feel both alarmed by and sympathetic toward her. From the plaque: Between 1963 and 1964 Niki de Saint-Phalle created a series of works denouncing the different statuses assigned to women: wife, mother, child-eater, whore and witch. The explanation is succinct, but the sculpture spills over with contradictions; to me it feels like something more fragile than a denouncement. In its melding of too-human and too-monstrous, it feels like an uncanny mirror. I find myself thinking about it again and again as the days pass.

*

One day, in the Palais de Tokyo bookstore, I stumble across a copy of Weight of the Earth, the transcribed cassette-tape journals of East Village artist David Wojnarowicz. I buy it, and from the moment I start reading, I am mesmerized.

In these tapes, Wojnarowicz is talking to himself, but he has a clear awareness of potential future audience. He isn’t interested in saying the right things in the right ways; he isn’t interested in pretending he’s less angry or confused or chaotic than he is; he isn’t trying to polish the rough edges for anyone’s comfort, least of all his own. His ideas of intimacy and power are shaped by the sexual encounters he had with older men, when he was a pre-teen and then a teen in the 1960s. Sometimes he portrays these as transactional, sometimes as consensual, always charged with a variety of potentials. Reading these sections, I can hear in my head an entire dissertation on trauma and sexual exploitation that would be applied to his experience through today’s lens. Whether or not that modern lens is correct isn’t my point; only that, in these tape journals, he doesn’t seem to see himself through it. And the fact that this occasionally makes me uncomfortable does not make it bad art.

*

I am troubled by how often people talk about likability when they talk about art.

I am troubled by how often our protagonists are supposed to live impeccable, sin-free lives, extolling the right virtues in the right order – when we, the audience, do not and never have, no matter what we perform for those around us.

I am troubled by the word “problematic,” mostly because of how fundamentally undescriptive it is. Tell me that something is xenophobic, condescending, clichéd, unspeakably stupid, or some other constellation of descriptors. Then I will decide whether I agree, based on the intersection of that thing with my particular set of values and aesthetics. But by saying it is problematic you are saying that it constitutes or presents a problem, to which my first instinct is to reply: I hope so.

Art is the realm of the problem. Art chews on problems, turns them over, examines them, breaks them open, breaks us open against them. Art contains a myriad of problems, dislocations, uncertainties. Doesn’t it? If not, then what?

*

I think we’re laboring under a moment in which many believe that the sole function of art is to provide moral guidance.

I understand how we got here. Our politicians and leaders have for the most part abdicated responsibility on this front – not in what they say (there’s always moralizing) but in what they’re caught doing later. An entire parade of celebrities has been similarly revealed to be mouthy, handsy monsters of hypocrisy. The arts, though underfunded, have a history of being a fallback battleground for American morality. And also, always, America is obsessed with the idea of virtue. Ours is a country founded on many myths, but one of them inarguably is purity: pristine forests, clear water, virginal women, God everywhere.

In 1990, Rev. Donald Wildmon and the American Family Association excerpted some sexy collage bits out of the paintings in Wojnarowicz’s NEA-funded exhibit “Tongues of Flame,” and sent a mass mailing to every member of Congress and 178,000 pastors, demanding that the NEA not fund gay pornography. Wojnarowicz, true to form, called them “a bunch of repressed five-year-olds” and pointed out that, if you’re asking the government to defend the ethics of where its money goes: “Public monies are being used to fund covert wars, to buy instruments of death.” And yet, though he won that case, he couldn’t defeat the ongoing American misconception that art must be entwined with Goodness.

I think about this on the days when I have script meetings in which – across a variety of media – people worry about something being too provocative, too morally ambiguous. The most popular pitch for how to fix it is that a key character, at a key moment, will get up and just deliver a great monologue about how they know they’ve been behaving badly, and how they plan to change. Another common suggestion is that other characters indicate for the audience that the behavior we’re witnessing is not right, in case there was any doubt. But if we expect every novel, play, film, etc. to be a PSA for Good Behavior, we lose access to the part of art that is most connected to our humanity.

That is to say: the part where we witness our flaws, our savage desires, our troubling predilections, our shame and longing, selfishness and hope. The parts where we are creatures in flux, caught between contradictions. The parts where, presented with what makes us uncomfortable, we encounter ourselves and each other newly in the discomfort.

Sarah Kane’s plays have haunted me for decades, not because I find them pleasant and enjoyable but because they push the limits of my ability to witness the collapsibility of geographies, the ways in which violences elsewhere or elsewhen inevitably become violences here and now. Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater makes me ask myself intimate questions about how trauma and power intersect inside one body, and specifically how I, as a genderqueer person, can be either fueled or destroyed by the multiplicities I hold. Hemingway’s oeuvre continues to mesmerize and frustrate me, because he has so little use for women and such damaged ideas of what is necessary for men. And yet more than anyone else, he has made me think about what it means to invent and perform and become the self we wish to live with; his entire body of work is a desperate self-conjuring.

We – as readers, as audiences, as visitors to places of art – are not entitled to stasis. Or: If some of us have created lives in which we feel entitled to stasis, I don’t want to participate in creating work that furthers this entitlement.

*

David Wojnarowicz, circa January 1989: “For the most part, [art] has become very shallow, very boring, and looks exactly like what it intends to disrupt… I wish society would just wake up, because it’s as if it’s a nation of zombies, as if everybody’s asleep… And my only feeling is that the dreams are becoming very, very boring and predictable.”

*

This is where institutions come in, because art does not exist in a vacuum. It is published, it is performed, it is judged worthy or unworthy of receiving cultivation and funding. I worry about a climate in which, fearing censure, institutions only support works of art that portray the values that their communities have deemed worthy. I worry about the prioritization of art that declares in bold what is GOOD and what is BAD, and how the audience – by thinking one set of things over another – can go from BAD to GOOD. When I say I worry about this, I mean I am seeing it more and more. Sometimes the BAD and the GOOD are defined by a liberal lens and sometimes by a conservative one, but in both cases the art suffers from its moral simplicity.

I hope that part of what residencies and cultural institutions do is court projects whose aims are manifold and murky, slippery and tricky, artists who are trying to figure out how to ask the hard questions, instead of being prepared to package and sell the “right” answers. Not because there is equal value in all forms of provocation – some are successful inquiries into our hidden natures and some are the artistic equivalent of gum in your hair – but because by valuing what disarms and unsettles over self-congratulatory moral binaries, we treat art as something that can truthfully reflect – and therefore change – our lives.

*

Omicron cases surge while I’m in Paris and the Russian invasion of Ukraine escalates. I hear that iodine is flying off the shelves of European pharmacies because of the fear of nuclear winter. It’s hard not to feel paralyzed. More and more, I’m depressed. I have to take myself out into the air and make myself look around: You are here and there is life. Catastrophe, but also life. I tell myself again and again: Don’t simplify.

Toward the end of the cassette diaries, after Wojnarowicz has been diagnosed with AIDS, he talks about depression, rage, waves of desire, paralyzing fear. And then, a recording from a road-trip somewhere in North Carolina. The air is filled with the smell of trees; he can see green and blue mountains superimposed against each other, rolling and endless. He says he had been wondering if, headed for a car-crash, he would hit the brakes or step on the gas. But then he nearly had an accident, and it turned out that his instinct was still to hit the brakes.

“This is life,” he says. “Let’s swim in it.”

Get notified when the next essay is published

Find all Why MacDowell NOW? essays here

Jen Silverman is a New York-based writer and playwright. Jen is the author of plays Collective Rage: A Play in 5 Betties, The Roommate, and Witch; the debut novel We Play Ourselves and the story collection The Island Dwellers (Random House); and the poetry chapbook Bath selected by Traci Brimhall for Driftwood Press. Additional work has appeared in Vogue, The Paris Review, Ploughshares, LitHub, The Yale Review, and elsewhere. Jen is a three-time MacDowell Fellow, and the 2022 recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts (Prose) and The Guggenheim Foundation (Drama).