MacDowell landed in my life like a meteor crashing onto the sidewalk before my feet. The impact spun me around, sent me heading in a totally different direction. An impact that changed everything I had planned, and who I thought I was.

It was 2017: I’d just been accepted into a prestigious professional development studio program at an art center here in Chicago, one that demanded two years of full-time commitment. I was elated. I’d been applying to that program for a long time. Just as I started to pack my studio to move to the center, kerchunk, I was accepted into a 3Arts-supported MacDowell residency. I was shocked. I’d never expected to win a slot based on my writing. In fact, I’d never applied to anything based on my writing. I was working on something I hoped would be a memoir, but had few expectations — I had decades of training in making pictures, but virtually none as a writer and was acutely aware of my lack of technique, not to mention my lack of progress. I’d filled out the application in the hopes of having more than two hours a week in front of my keyboard. I was so surprised by being accepted that I figured I’d gotten the pity vote, and that the jury was just playing a round of Be Nice to the Poor Cripple. I actually wrote to MacDowell administration and asked if that was the case! I was told in no uncertain terms that the panel decided on merit alone. I thought, yeah, right — but I packed anyway. The Chicago studio program allowed me to delay my residency until I got back from New Hampshire.

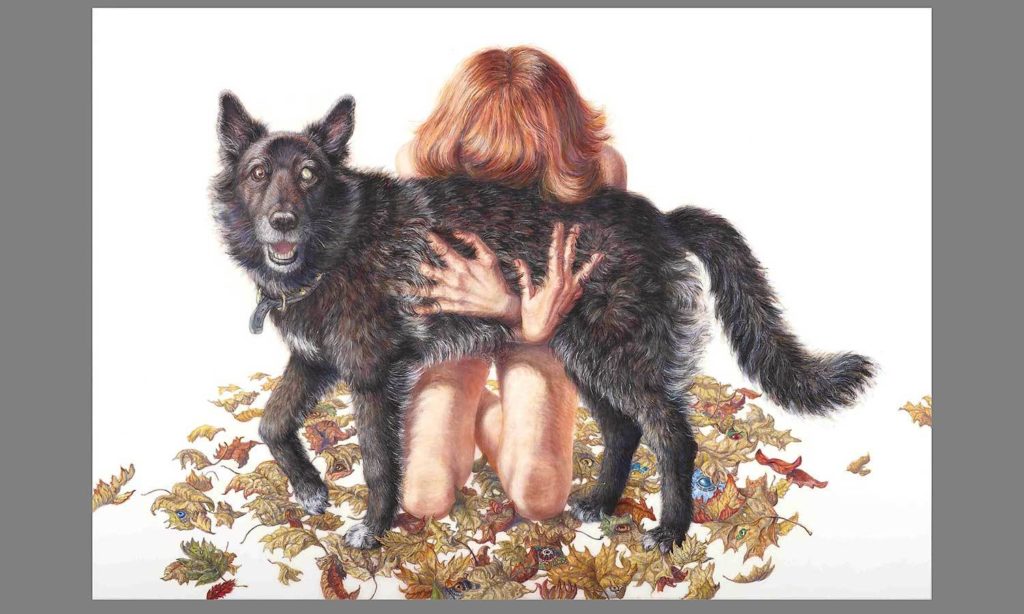

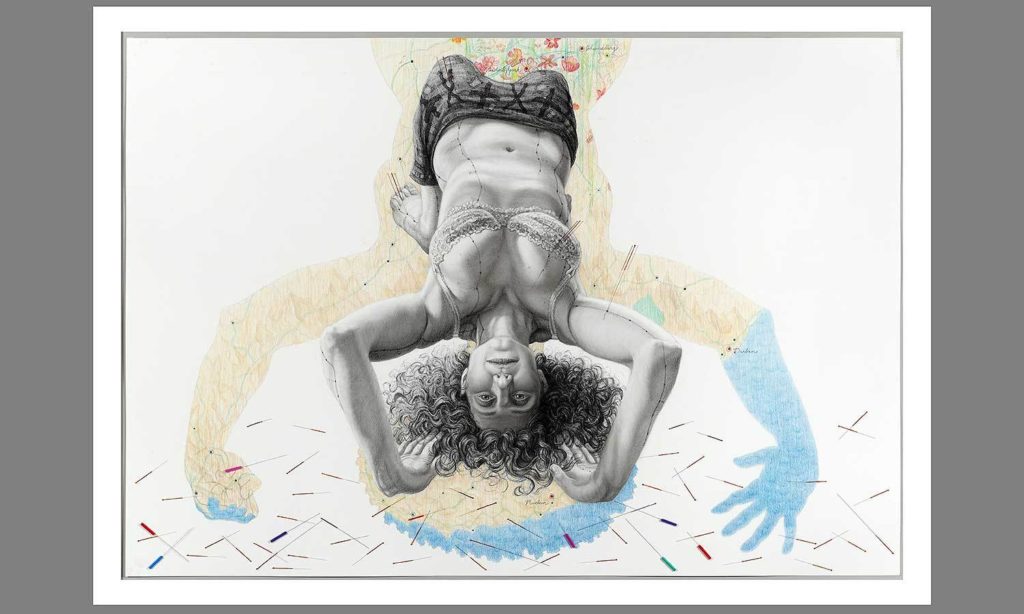

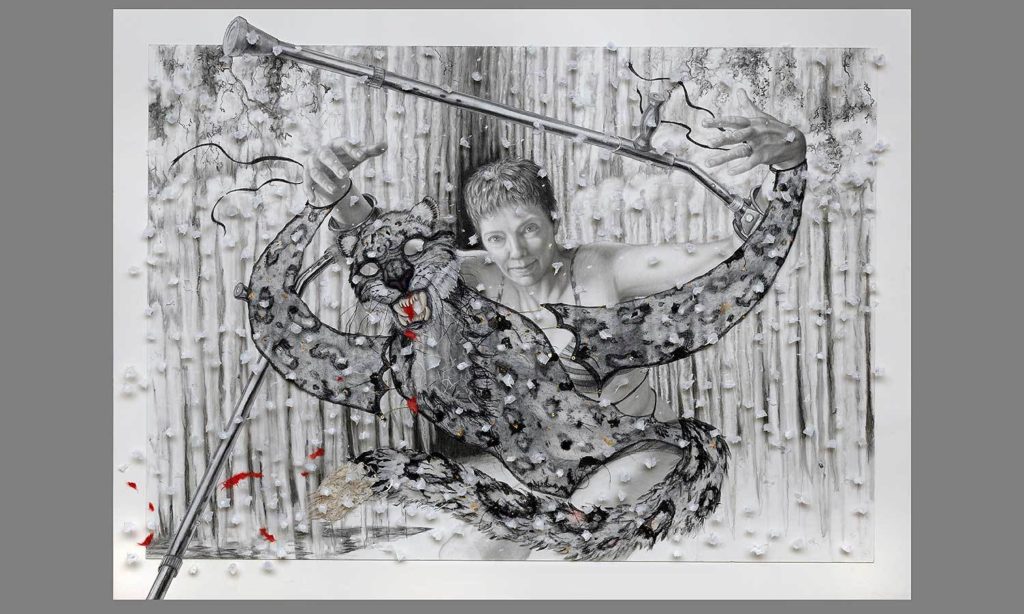

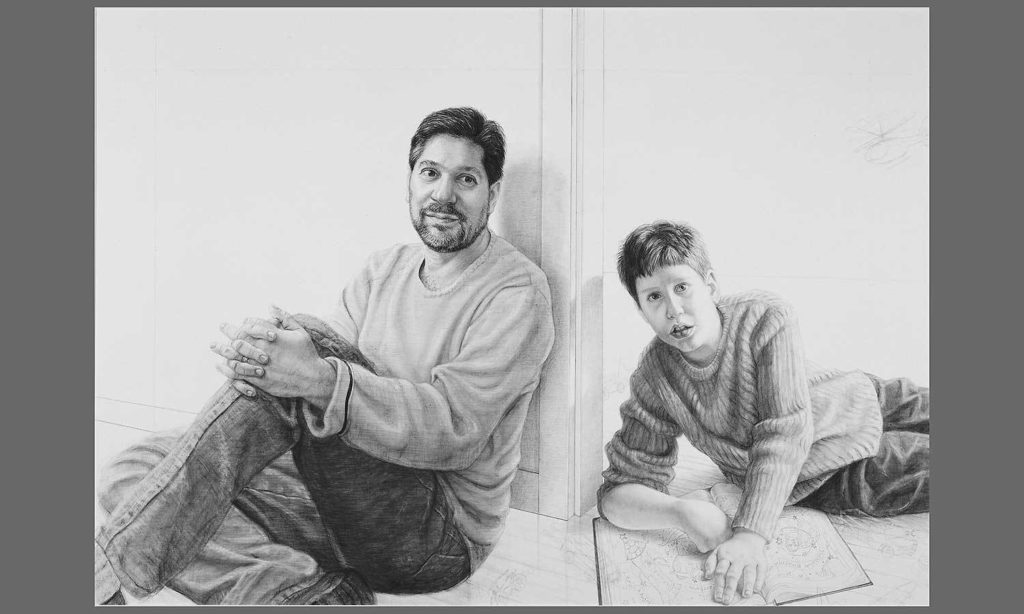

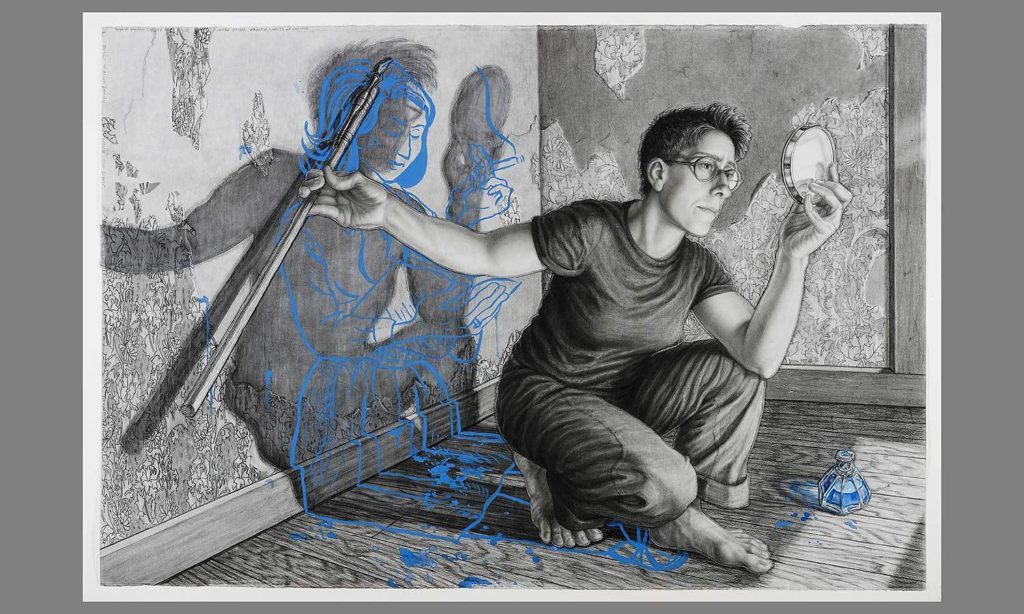

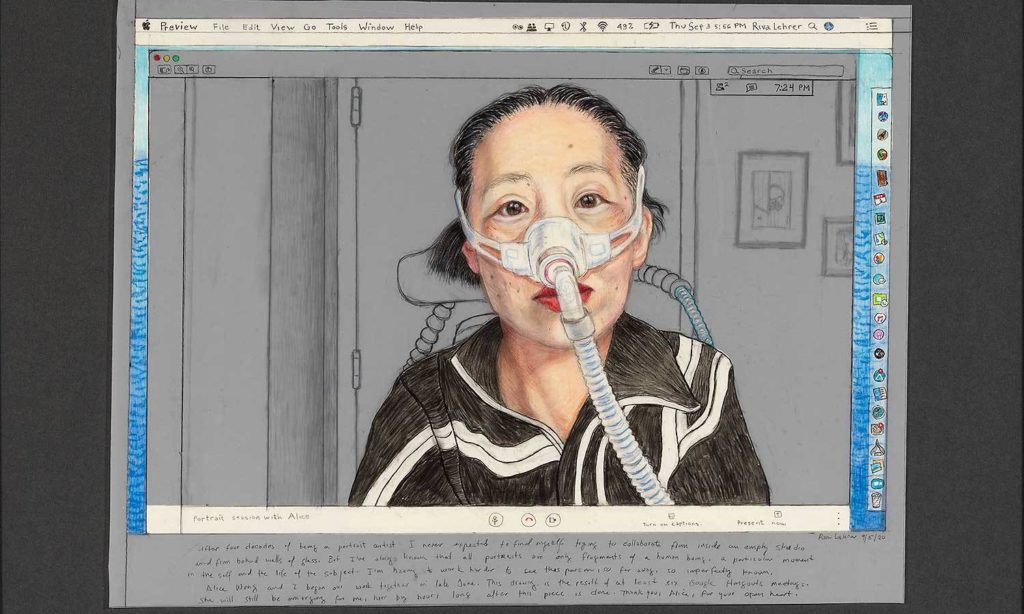

Frankly, I was disoriented. I would never have said I was a writer. My public talks, lectures, and essays were keyed to my career as a visual artist. I spoke on my portraits and the reasons why I choose subjects who live under stigma, particularly the disabled, people in the LGBTQ+ community, people who identify as BIPOC, and other self-defined social outliers. I am a queer, disabled woman. My story is entangled with theirs. We are told that our bodies are mistakes — or that the way we perform our bodies threatens the social order. Told that we must change, be cured, be invisible. I make portraits as proof: We exist. We are.

I felt like my public writing yanked me into what I call the explain-y voice, the didactic drone of the lecture hall. An old boyfriend used to tell me, write your story like an adventure tale. I was working on a book in search for a storytelling voice that left the drone behind.

I entered MacDowell in a frenzy of imposter syndrome. This faded away under the spell of the land. I lost myself in the deluge of green, the immersion of forest color that sings with unfamiliar birdsong. Pale-blue Mount Monadnock watching over us, our resident deity. I shared my morning coffee with unfazed deer, under dapples of sun like stars on the ground.

But the people? I was terrified. My cohort was composed of writers and artists whose accomplishments made me wonder, again, if my presence was a fluke.

There were other snags. My disability is spina bifida. My partner (at the time) and I spent hours at the Ocean State Job Lot trying to outfit my studio, Monday Music, for my physical needs. I felt uncomfortable asking the staff for the accommodations I needed, but they were so responsive that they asked me to write my suggestions for hosting disabled residents.

How strange it was to have nothing to do but write. To make sense of my jumbled 60 years. I stitched together scraps of memory into a story as a story, not a series of points to be delivered in a conference ballroom. I tried to explain my life as a monster: A Golem. A creature built by surgery. Constructed by the will of others. A being that began to build itself.

A hundred hours of silence in the green, while my hands delivered what my mind produced.

That residency was, quite possibly, the best month of my life.

Yet underneath this joy was the realization that if I went home and entered the studio program, I would never finish my memoir. I decided to sign up for an evening reading as a fact-finding mission. I asked the cohort audience to tell me the truth: if my writing was nothing but hobby-level self-indulgence, I needed to know. I said, please be honest, I have a perfectly acceptable future waiting for me if I’m not any good. I read a chapter about a tragedy that befell my mother. People insisted that I finish writing the book. By then I’d gotten to know almost everyone. Weeks of breakfasts jostling over the coffee urns, asking how’s your painting going? Get any pages done? Evenings of wonderful dinners that (in my case) added five pounds to my midsection, ending with a performance, a reading, a studio visit. Many of my cohort are still my friends today; we follow each other’s work and support each other as we can. So, foolish or not, I decided to believe them. I swallowed hard, wrote to the studio program, turned them down, and committed to writing Golem Girl.

Thus began a cascade of miracles. I wrote an op-ed for The New York Times; this won me an agent; he brought me to the attention of One World, an imprint of Random House, and all of a sudden the book was real. All this took place within the six months following my residency. I was a dreidel at Chanukah, spin, spin, spin.

Books about disability are rarely successful, unless they tell an “overcoming” narrative, in which the writer contracts a disease or loses a body part, yet still manages to free-climb the Grand Canyon. Or invents a cure for their very disease. Golem Girl doesn’t overcome. It insists on the complexities of embodiment, the gifts it bestows and the prices it demands. The book is full of color images of my portraits (nearly a catalogue raisonné), making it an art book as well. It tells the stories of my subjects. My purpose, whether as an artist or a writer, is to make us visible in the way that we choose.

Which brings me to “Why MacDowell Now?” I could never have known that three years later, we would all — young or old, able-bodied or not — be rendered invisible, locked away in our houses, shrouded by masks, keeping perimeters around our bodies like covert moats. The disabled were told to hide, because we weren’t guaranteed medical treatment. We were dispensable. Our pathetic “quality of life” was insufficient to qualify us as worth saving.

Now, as the vaccines roll out, disabled people are not prioritized on statewide tiers, no matter our vulnerabilities or impairments. Once again, the message is that it’ll be no loss if we succumb. We can’t hit the streets in protest, because for many of us, the public sphere is beyond dangerous. Our houses may not be much safer, if we have medical personal assistants that come and go, largely unvaccinated, carrying danger inside our walls.

Almost every day I hear from people who have read Golem Girl. They say it’s changed their understanding of disability. I’ve been very fortunate. I’ve been asked to speak on NPR, the CBC, and the BBC, and interviewed and reviewed in numerous print outlets. The memoir won the Barbellion Prize and is nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Without MacDowell, there would be no Golem Girl. Without Golem Girl, I’d never have access to such public platforms.

MacDowell sent me on an adventure that became a quest.

I say, again, we are.

That’s why.

Riva Lehrer is a nationally known visual artist who collaborates with people from the Disability, LGBTQ, and other marginalized communities to create narrative portraits that address issues of stigma and redefinitions of beauty. While an artist-in-residence at MacDowell in 2017, she completed a substantial portion of her memoir, Golem Girl.