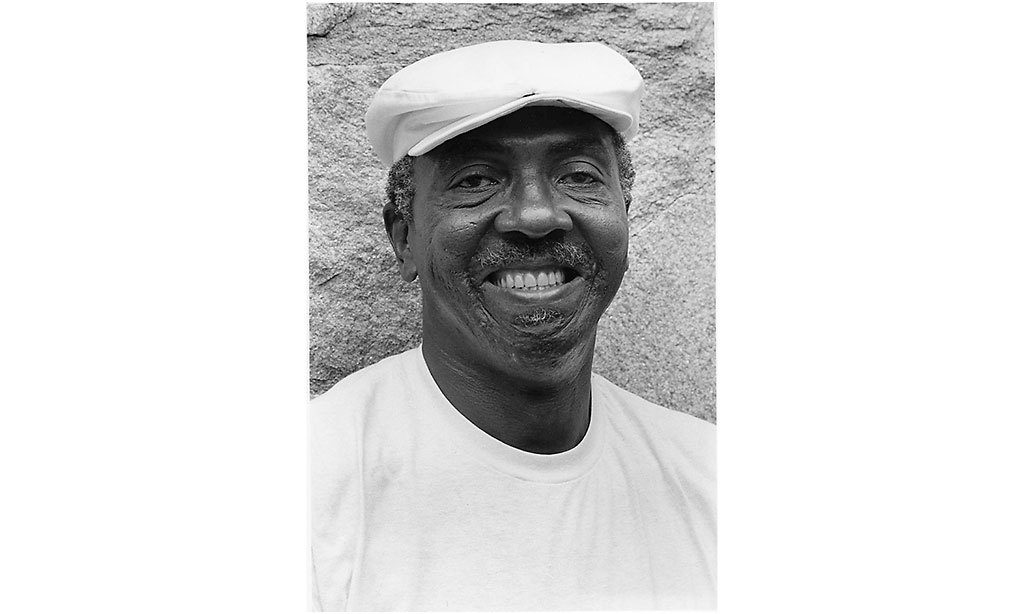

Etheridge Knight’s Poetry Gives America the Truth of Being Black

By the time Etheridge Knight arrived at MacDowell in the summer of 1986, he had dropped out of high school, been wounded as a soldier in Korea, developed a drug addiction as a result of his shrapnel wounds, and spent eight years in Indiana State Prison for a 1960 robbery conviction. He had also published a handful of poetry collections, was nominated for the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, and was widely celebrated for his art. According to Terrence Hayes, a poet and professor of English at NYU, Knight’s “biography is a story of restless Americanness, African Americanness, and poetry. It has some Faulknerian family saga in it, some midcentury migration story, lots of masculine tragedy, lots of soul-of-the-artist lore.”

Knight started writing during his sentence, working for a prison newspaper and submitting and publishing poems. He also struck up relationships with the Black American literary community and was visited by many significant writers at the time. His first collection, Poems from Prison (1968), was published the same year he emerged from his incarceration, and much of the work looks at imprisonment as a type of contemporary enslavement. On the back of the first edition is a quote from the author: “I died in Korea from a shrapnel wound, and narcotics resurrected me. I died in 1960 from a prison sentence and poetry brought me back to life.”

After the publication of Poems from Prison, Knight’s star rose quickly, and his writing was “another excellent example of the powerful truth of blackness in art,” according to Shirley Lumpkin in the Dictionary of Literary Biography. “His work became important in Afro-American poetry and poetics and in the strain of Anglo-American poetry descended from Walt Whitman.”

Knight married poet Sonia Sanchez after his 1968 release from prison. She was one of a handful of luminaries who had visited him while he was serving his sentence, and both were important members of the poets and artists connected to the Black Arts Movement.

In the Los Angeles Times Book Review, Peter Clothier considered Knight’s poems to be “tools for self-discovery and discovery of the world — a loud announcement of the truths they pry loose.”

According to Knight, a definition of art and aesthetics assumes that “every man is the master of his own destiny and comes to grips with the society by his own efforts. The ‘true’ artist is supposed to examine his own experience of this process as a reflection of his self, his ego…. White society denies art, because art unifies rather than separates; it brings people together instead of alienating them…. [This European aesthetic dictates] the artist speak only of the beautiful (himself and what he sees); his task is to edify the listener, to make him see beauty of the world.” Instead, wrote Knight, Black artists must stay away from this: “the red of this aesthetic rose got its color from the blood of Black slaves, exterminated Indians, napalmed Vietnamese children…. [the Black artist must] perceive and conceptualize the collective aspirations, the collective vision of Black people, and through his art form give back to the people the truth that he has gotten from them. He must sing to them of their own deeds, and misdeeds.”

Read more about Knight at the poetry foundation

Read the poem "Hard Rock Returns to Prison from the Hospital for the Criminal Insane"

Read an excerpt of a March 2015 lecture "The Space Between Everything" by Terrance Hayes published in The Paris Review

The Idea of Ancestry

1

Taped to the wall of my cell are 47 pictures: 47 black

faces: my father, mother, grandmothers (1 dead), grand-

fathers (both dead), brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts,

cousins (1st and 2nd), nieces, and nephews. They stare

across the space at me sprawling on my bunk. I know

their dark eyes, they know mine. I know their style,

they know mine. I am all of them, they are all of me;

they are farmers, I am a thief, I am me, they are thee.

I have at one time or another been in love with my mother,

1 grandmother, 2 sisters, 2 aunts (1 went to the asylum),

and 5 cousins. I am now in love with a 7-yr-old niece

(she sends me letters in large block print, and

her picture is the only one that smiles at me).

I have the same name as 1 grandfather, 3 cousins, 3 nephews,

and 1 uncle. The uncle disappeared when he was 15, just took

off and caught a freight (they say). He's discussed each year

when the family has a reunion, he causes uneasiness in

the clan, he is an empty space. My father's mother, who is 93

and who keeps the Family Bible with everybody's birth dates

(and death dates) in it, always mentions him. There is no

place in her Bible for "whereabouts unknown."

2

Each fall the graves of my grandfathers call me, the brown

hills and red gullies of mississippi send out their electric

messages, galvanizing my genes. Last yr/like a salmon quitting

the cold ocean-leaping and bucking up his birth stream/I

hitchhiked my way from LA with 16 caps in my pocket and a

monkey on my back. And I almost kicked it with the kinfolk.

I walked barefooted in my grandmother's backyard/I smelled the old

land and the woods/I sipped corn whiskey from fruit jars with the men/

I flirted with the women/I had a ball till the caps ran out

and my habit came down. That night I looked at my grandmother

and split/my guts were screaming for junk/but I was almost

contented/I had almost caught up with me.

(The next day in Memphis I cracked a croaker's crib for a fix.)

This yr there is a gray stone wall damming my stream, and when

the falling leaves stir my genes, I pace my cell or flop on my bunk

and stare at 47 black faces across the space. I am all of them,

they are all of me, I am me, they are thee, and I have no sons

to float in the space between.