My Coronavirus Occupation

By Nell Painter

Coronavirus came to occupy my art in Fondazione Bogliasco’s villa above the Ligurian Sea where I was in an artist’s residency between mid-February and mid-March of this year. My husband Glenn accompanied me in this Italian world contrasting so sharply with the dense woods of land-locked rural New Hampshire that I savor at MacDowell.

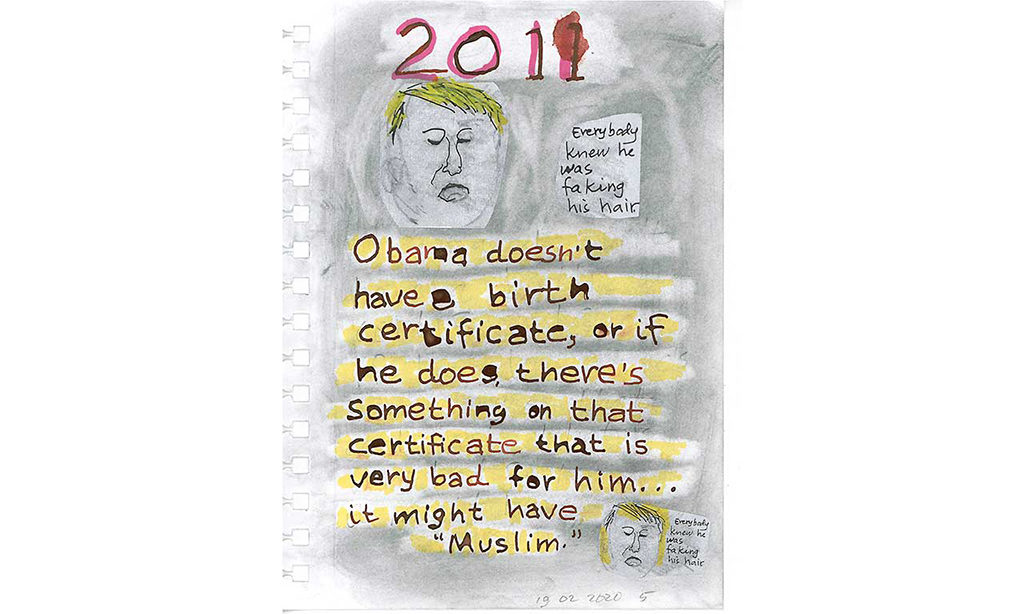

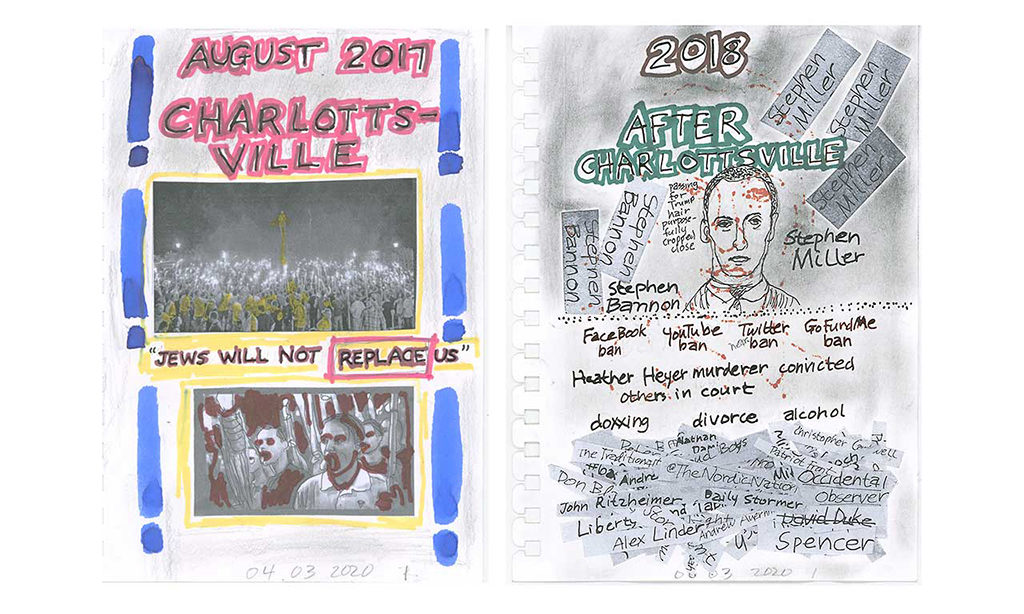

My project was an artist’s book, a visualization of my research on the history of white people in the U.S. today. When I started drawing Trump, I was in a sumptuous library beside floor-to-ceiling bookshelves of leather-bound complete editions of classic French authors. Gentle portraits of Bogliasco founders on the library’s walls encouraged and surveilled me as I revisited the shock of Trump’s campaign and the ugly white nationalist rhetoric that made him a sensation.

The Villa at Fondazione Bogliasco

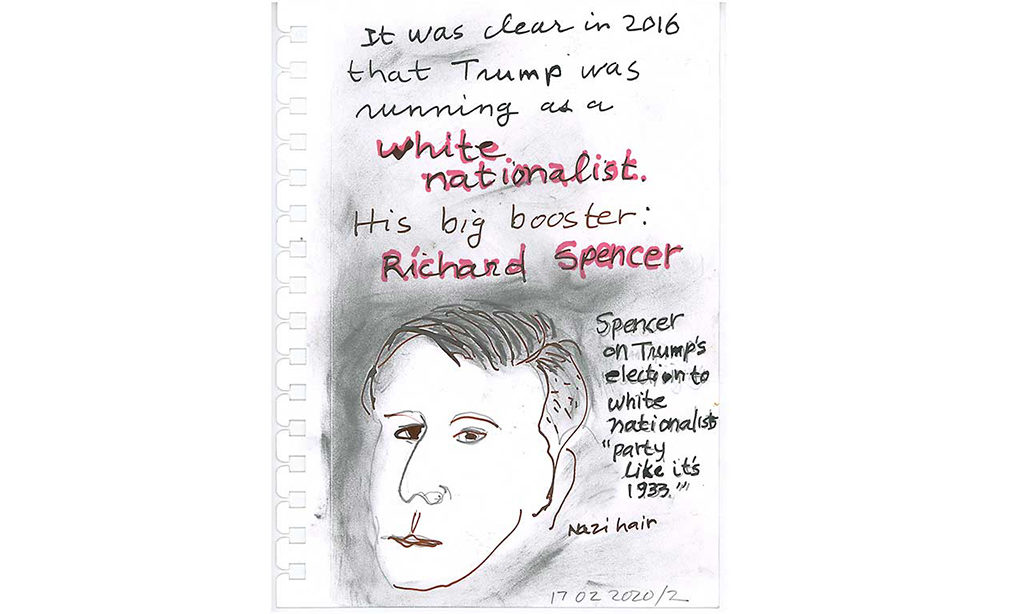

In that lovely library I labored for hours poring over online sources for the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Anti-Defamation League, and newspapers describing Trump’s supporters. After a week of research, I focused on the ubiquitous Richard Spencer in his “fashy” hair, a nouveau fascist fashion statement.

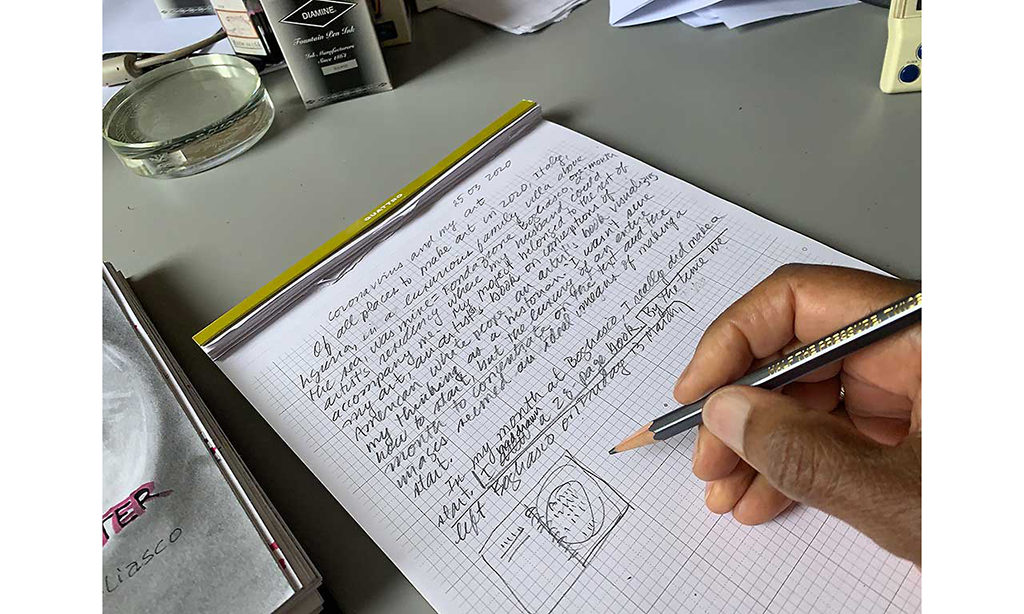

By the time we left Bogliasco on Friday March 13th, I had drawn a 28-page first draft my book.

As at MacDowell, mealtime conversations were generally collegial, with U.S. politics out of bounds. We discussed Deborah’s graphite drawings, Iris’s choreography inspired by protest and crackdown in Athens, Italian housing policies and refugees featured in Ludovica and Arianna’s films. Chris explained how the sound of applause became wave music. Theodora and I talked a lot about our shared passion for the paper in her puppets and my drawings. We traded thoughts about Genoa’s museums, markets, and its Müller art supply store.

A party of us took the local train to Acquasanta to visit the Museo della Carta, a museum dedicated to paper making, a major industry in the Genoa region until the 1970s, when everything local, not just papermaking, collapsed as open markets brought cheaper paper products from elsewhere. Above the Via Aurelia in Bogliasco, greenhouses also disintegrated, another victim of globalization.

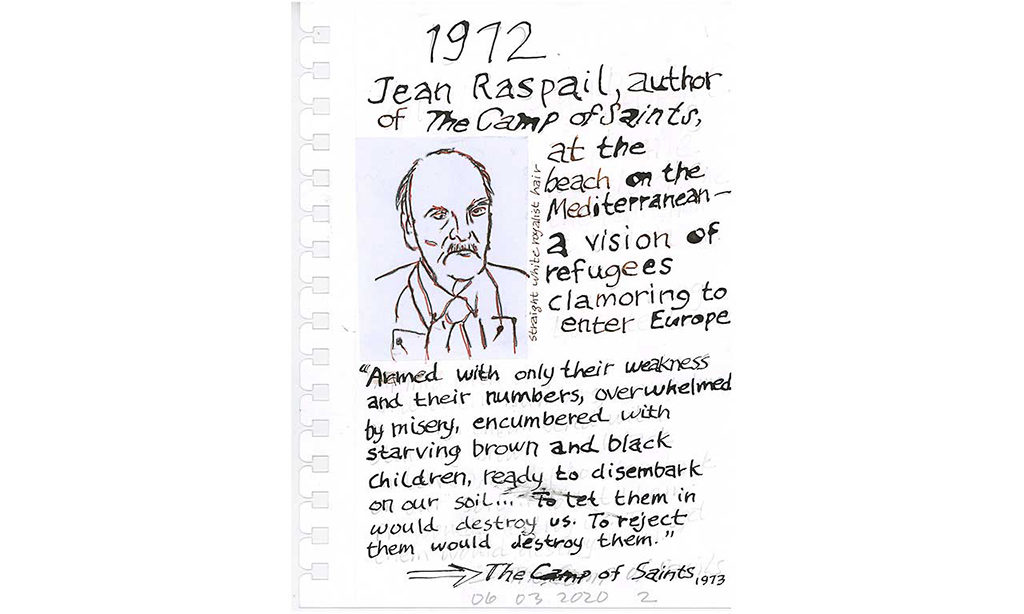

I was sometimes a terrible dinner table conversant on account of my immersion in Trump’s white nationalists. My subjects were odious: Steve Bannon, Pat Buchanan, and Stephen Miller and their “invasion” and “replacement” obsession with a vile 1970s French novel, The Camp of Saints. That pornographic and xenophobic dystopia, overflowing with bloody images of racial hatred, fascinated Trump’s people. They recommended it to their followers as true portents of a white people’s future without walls and that might be open to invasion.

For Trump’s white nationalists, it was the swarthy hordes who menaced civilization. Yet we had only been in Bogliasco a couple of weeks when a new menace to civilization appeared in Italy. The phenomenon of coronavirus, hitherto seemingly an Asian problem, penetrated Lombardy and the Veneto. In Bogliasco we were feeling safe in a charming little seaside village to the south of Italy’s industrial region. Liguria wasn’t in the most directly affected regions, but schools, libraries, and museums were shut down for a week just in case.

Soon the plague was creeping into our dinner table conversation as a fact to be taken into account when planning visits beyond Bogliasco. We watched Luchino Visconti’s 1971 movie version of Death in Venice and discussed the film’s arch iconography and drama-queen depiction of same-sex attraction during a cholera epidemic.

So far as we were concerned, our villa and little town were functioning pretty much as usual with shops and the Tuesday street market open. As long as the weather was fine, I encountered lots of people on my walk along via Capolungo to the little port in neighboring Nervi. In my beautiful family library, I worked steadily on my drawings.

My dinner table conversation improved with my discovery that the obscene and murderous “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville in 2017 had badly crippled American white nationalism. A transition from ghoulish display and murder to online banishment, exile, divorce, and alcoholism tamped down white nationalist braggadocio.

By early March northern Italy’s tragic coronavirus vulnerability was obvious, and we began to feel its trespass. Cracks started appearing in the Bogliasco fellowship’s stability. Shira, already scheduled to return to Israel early, left even earlier. Others found a need to be elsewhere. Chris and his wife Jenalie departed. As Glenn’s university was recalling faculty and students from overseas, he, too, was wanting to go home. But not me.

It was only the 1st of March, I countered. I had nearly two weeks left in my residency. My project was well under way but nowhere near complete. After my research online, I was just getting a decent start on the drawing. Leaving now would disrupt my work and break my momentum. Against being marooned in Italy, I weighed freedom from food shopping, cooking—our Bogliasco meals of regional Italian cooking—pesto alla Genovese, saffron risotto, fresh fish, local cheeses, and fruit all tasted divine—and the events I’d have to attend at home.

We didn’t leave, though others did, Iris to Athens, Azza to Beirut, Ludovica and Arianna to Rome. I continued working as though as safe and sheltered as I would have been at MacDowell. I couldn’t know then that the coronavirus would soon interrupt and halt MacDowell Fellowships for months to come. I kept drawing.

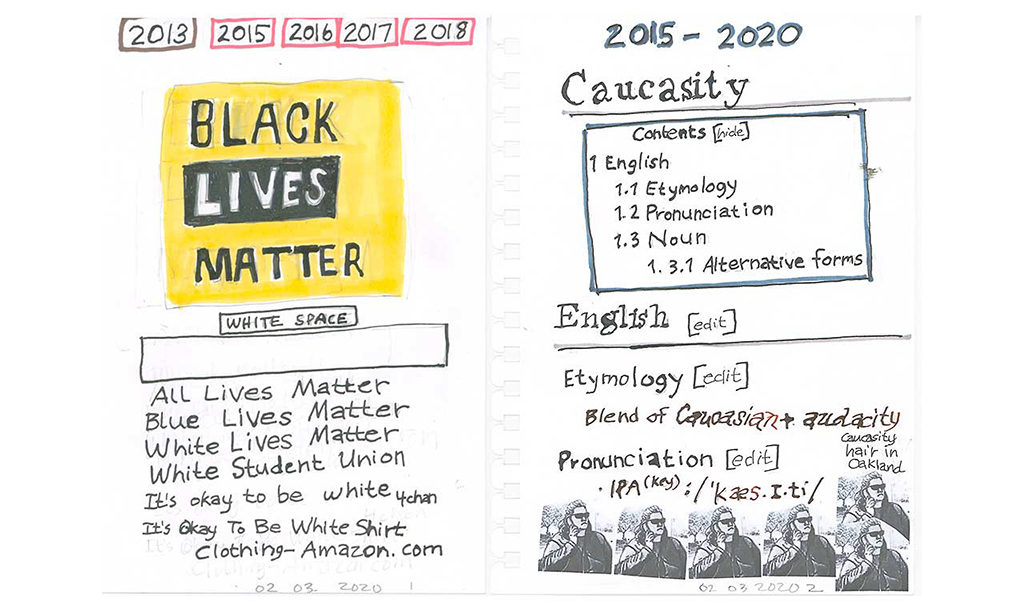

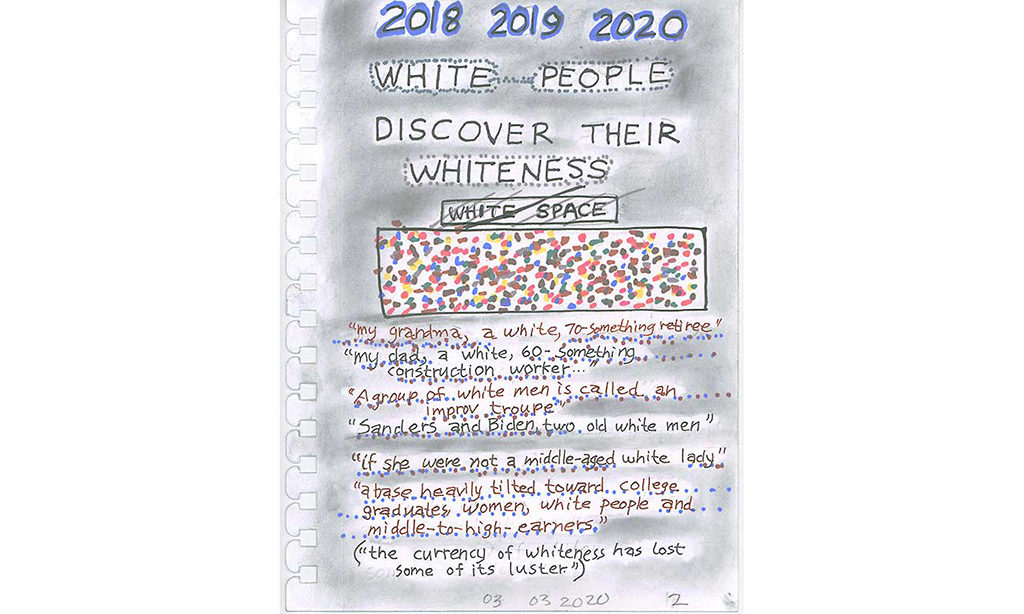

On March 3rd, I made drawings comparing the conventional wisdom on Trump’s allure in 2015-2016 to the conventional wisdom a few years later. From it’s all-economic-those-poor (white, unsaid)-people-who-lost-their-jobs reasoning to plain race resentment.

As our Bogliasco numbers shrank, I contrasted Trumpist logic to changes in how Americans were talking about white people, with the fact of white identity newly visible.

My last page, though not the last page I drew, said “white people discover their whiteness.” It reworked the Black Lives Matter page’s exclusive white space into a space now occupied by other colors and the sign “white space” barred as in No Parking.

Though the scary fact of coronavirus was really sinking in, we reached for normality — or was it a self-conscious farewell to what had been our sheltered seaside-villa normal? We who were left took the local train — the trains were still running, though not to be taken for granted — to Camogli for lunch by the sea. Squeezed under an awning, our server photographed us sitting close together in a restaurant above a mass of sunbathers stretched out on the beach. This was March 8th, the day before coronavirus broke into everything to become the gigantic, overweening fact of life: what was closing, what remained open, how to get home. Coronavirus was strangling everything.

After Iris left early for Athens, Rob and Claudia, and Deborah and Michael decided they really must return to the U.S. now, despite severe travel disruptions. Over in the Bogliasco Study Center office, each change of plans demanded hours of staff efforts changing Fellows’ travel itineraries. At the lunch table, conversation traced and retraced whose travel succeeded to go where and whose failed.

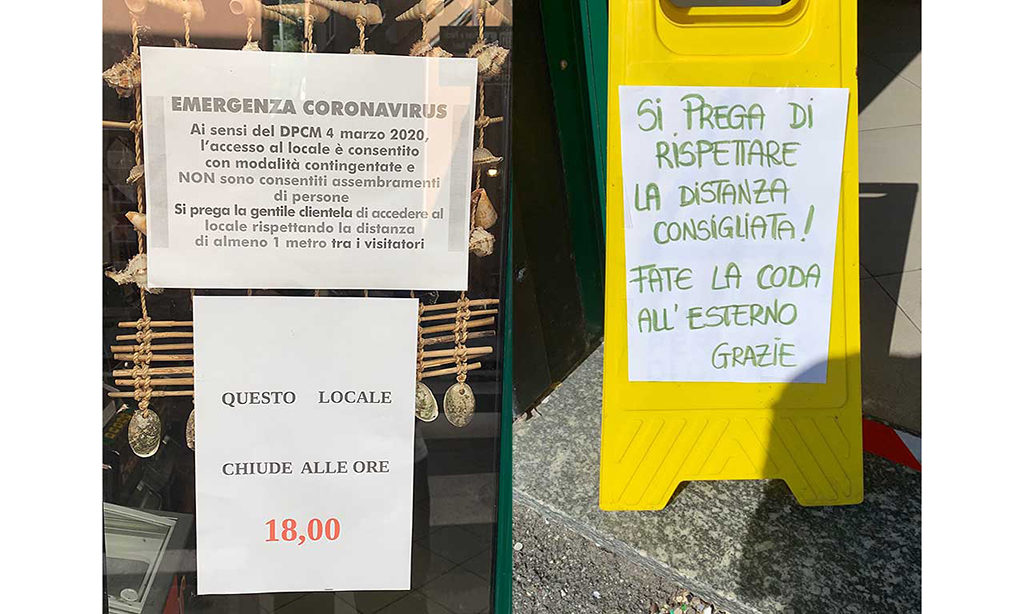

The weekend of March 7-8 wrought a behavioral revolution, as signs of the coronavirus invasion reached the villages of Bogliasco and neighboring Nervi.

As throughout all of Italy now, businesses staying open had to limit the number of people allowed inside at one time and to close by 6 p.m. Soon businesses had to close down entirely. On Via Capolongo fewer people strolled beside the sea; one or two of them now wearing masks. No one sat enjoying the sunshine.

The impending exodus encouraged Glenn’s determination to try to get us out before Friday the 13th. Still reluctant to leave my drawings, I acquiesced. But with Ivana and Valeria occupied with Fellows’ complicated needs, Glenn’s attempts to reach Air France meant fruitless hours on hold. He failed. We simply could not leave sooner than scheduled on the 13th, and we were stuck. Our original departure was the only departure we had. I was still not afraid, though Glenn second-guessed himself repeatedly. We went to bed Wednesday night the 11th resolved to pack on Thursday and stick to our original departure on Friday.

Then a text pinged my phone at 3:30 a.m. on Thursday March 12. President Trump had announced a ban on all flights arriving from Europe — only travel from the UK was permitted — to go into effect at midnight Friday the 13th.

Now I panicked.

We were scheduled to arrive at JFK from CDG Paris at 7:55 p.m. on Friday. Too close, way too close. I cursed myself for valuing work over departure. Would a delayed flight maroon us in Europe for who knows where, for who knows how long? I should have closed up my work and prepared to go as others were leaving! I should have clamored for four hours for Ivana and Valeria to advance our leaving from the very last day! How, now, to pack up unruly art supplies, books, and clothes in a hurry and try to get out on the 12th? Impossible.

On Thursday the 12th we were awakened at 5 a.m. by Theodora and David bumping down the stairs for their taxi to Genoa and train to Nice before Italian trains stopped running. I was back asleep as Deborah and Michael set off for Rome, and Rob and Claudia met their taxi to Genoa airport.

On our day to pack up, we were the only Fellows left at Fondazione Bogliasco closing up around us. Literally. We felt guilty for still being there needing the staff to look after us. No other Fellows were there to share a last amaro. Glenn and I sat alone at the big dinner table. We didn’t tarry for after-dinner coffee.

Finally Friday morning came, and we left for the Genoa airport by taxi and in masks and gloves furnished by the driver. Once our taxi’s doors closed, the Bogliasco study center closed up definitively. All over Italy as we were fleeing, millions were falling ill and thousands were dying in a country turned into a hospital, into a morgue.

Awaiting our flight in the Genoa airport, I discovered I could knit in masks and gloves, a skill I hoped never again to need, as our departure went smoothly. The airport police inspected our masked and gloved persons proffering travel attestations and let us board our flight to Charles De Gaulle airport in Paris. We got the last flight from Genoa airport to any place, including the UK, and made our CDG-JFK flight without incident, arrived at JFK well before Trump’s deadline, which, in fact, turned out to exempt U.S. citizens. No matter. After Friday the 13th, all flights to JFK from CDG were cancelled. To our great surprise, JFK seemed relatively uncrowded, even easy. Our line for customs was the shortest we’d ever seen, and the agent only smiled when we said we had come from Italy.

On our way home from the airport in record time, the NJ Turnpike never looked so good. Baggage, including American Whiteness Since Trump and my computer and art supplies arrived the next day, allowing us to drive home to the Adirondacks on Saturday March 14th. Coronavirus facts had not yet hit the U.S. as we self-quarantined at home up here for 14 days.

With everything cancelled at least into May, I had abundant time to make art, didn’t I? On first thought, freedom made me giddy. On second thought, I had time, yes, but Initiative, zero. I was completely inert.

I could not make art. I could not write. I could not answer email. Coronavirus had invaded my consciousness and replaced my mental energy with torpor, set lethargy where I used to take inspiration to think and to draw. I sat in my corner toggling ceaselessly between Facebook and The New York Times, mindlessly knitting and listening to 45 hours of an interminable audiobook on the USSR between the revolution and Stalin’s purges, a book on scary times that seemed so appropriate to my mood. Echoing friend Billy with the same anxious lethargy, I was both obsessed and deflated. Amidst mounting uncertainty, accumulating illness and death, and the president’s lying malfeasance, my collapse lasted well into April.

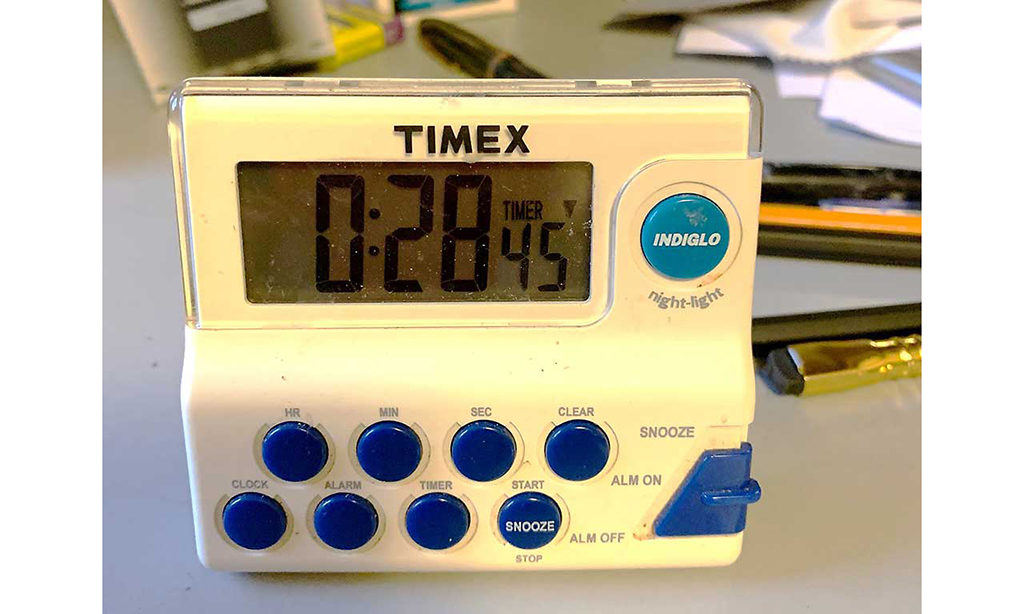

Only now am I finally able even to begin to recover from funk and to write this, thanks to a hack for addressing paralysis taught me by my very dear friend Thad: Set a timer for 15 minutes and sit yourself down before your materials, committing only to that limited duration.

Don’t try to make yourself write or draw. It worked. Three 15-minute sessions freed up my writing hand. I worked up to 30 minutes at a time, writing by hand, in pencil, my favorite means of starting anew.

In recent days our Adirondack neighbors have let us know one new thing though: In our cars bearing New Jersey license plates, we are regarded suspiciously as summer people invading from plague-stricken New Jersey. Now I’m an invasion, I with my brown face, a brown face that Jean Raspail and his Trumpian admirers — Buchanan, Bannon, Miller — would quickly recognize as the invasive face of an invasive body.

The nationwide invasion of coronavirus, an invasion of a strange inexorable force, has become so obvious that I now recognize my fascination at Bogliasco with The Camp of Saints’ lurid descriptions of invasion and replacement. Coronavirus has invaded our world and laid siege to day-to-day life through not only illness and death, but also filling us with unknowing.

Nell Painter (16, 19) is the author of the best-selling The History of White People, a memoir entitled Old in Art School, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle autobiography award and was appointed Chairman of the Board of Directors of The MacDowell Colony in 2020.